“If we don’t know where we’re going, it can be helpful to know where we come from.”

– Jostein Gaarder

Jul. 13, 2018 - Often, when one is lost or unsure, we look back to gain a sense of perspective on who we are and where we’re going. But what if the place you began is as much an enigma as where you are going and who you’re meant to be?

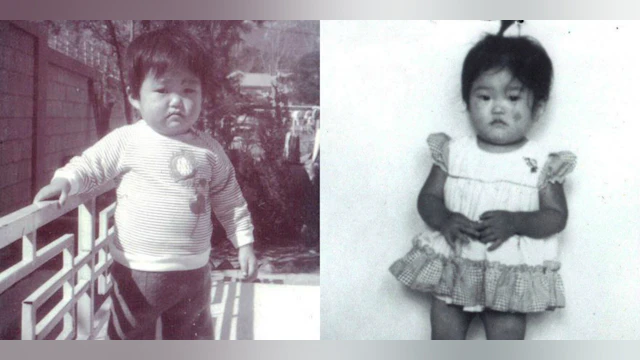

I’ve been told that my life started in Seoul, South Korea, born to a family who abandoned me at the age of two outside of a police station. I was taken to a local orphanage where I lived for a year before immigrating to the U.S. I have no memories of my birth parents, or of the country I lived in for almost three years of my life.

After a year in an orphanage, I was adopted by an American family who lived in Fergus Falls, Minnesota. Social workers and adoption counselors primed my family to anticipate a period of adjustment, assuring them that transitioning an international adoptee into a new country where everything felt unfamiliar, strange, and sometimes frightening would present challenges. In the months following my arrival, my parents naturally attributed my early episodes of uncertainty and fear to the normal process of settling into my surroundings.

But as time went on, those moments failed to diminish, and gradually increased in frequency and duration. I existed in a chronic state of worry and anxiety. Adding fuel to the fire was the fact that I was only one of a few minorities being raised in a small town. In spite of my family’s support, the lack of cultural diversity often played out in ugly ways. On my first day of kindergarten, a second grade boy taunted me the entire bus ride, screaming, “Pancake face! Pancake face! Look at that chink’s flat face!” The other children simply watched me shrink in my seat.

My parents did their best to protect me from these kinds of encounters, but the intangible worry and fear I felt began to shape itself into unanswered questions: “Where do I come from?” “What if no one likes me?”, “What if I don’t fit in?”, “What if I never fit in?”

By the time I turned twelve, my discomfort in my own skin became unbearable. I moved through each minute feeling like I was strapped into the vertical climb of a roller coaster, with every second ratcheting up with no sense of emotional release. Over time, my anxiety manifested into a deep depression, and I found myself having suicidal ideations.

I confided in two of my closest friends, believing our conversations would never go beyond the three of us. But fearing I would act on my thoughts, they reached out to the school counselor and my parents. I still remember the looks on my parents’ faces when they confronted me: they were terrified and heartsick.

I assured them it was nothing. As a minority I had spent years attempting to blend in. I knew my Asian “pancake face” already set me apart from everyone around me. I believed that publicly acknowledging my anxiety and depression would make things even worse.

I earned a music scholarship to a small private college in the Midwest. I hoped that the shift in environment would help me find some sense of self, some respite from my unrelenting self-doubt, and maybe even peers who could relate to me. But the change only triggered a new level of anxiety. By the time I turned 21, I was emotionally and physically depleted. I had spent a lifetime of fighting to make it through every minute of every day, and I couldn’t find the strength to do it anymore. Four months after graduating with honors from college and getting engaged, I attempted suicide.

My family and fiancé were distraught and adamant that I seek professional help. I agreed to visit a counselor, and started a regimen of anti-depressants, but I was humiliated and believed I had failed on every level possible.

Over the next several months, I showed up for my counseling sessions, but never fully committed to my treatment. I also held onto a hidden fear I had never shared with anyone: What if my birth parents were mentally ill? What if that was the reason I was given up for adoption? What if this was simply my legacy and I would never get better?

Eventually, my resistance to getting better took its toll. Before the year ended, I had lost both my job and my fiancé.

In the years following, I went on and off anti-depressants and started and stopped with a handful of therapists. I began to wonder if I would be riding this roller coaster until I just couldn’t take it anymore.

But a small part of me held onto a spark of hope that things could be different.

In the fall of 2014 I pushed myself to do something well outside my comfort zone: I volunteered for our city’s annual AFSP Out of the Darkness Walk. It seems counterintuitive, but I believed that even though the trajectory of my own life seemed impossible to change, perhaps I could help others.

I anticipated focusing entirely on helping to organize the walk. But working side by side with my peers was transformative and unexpected: people talked about depression, mental health and suicide openly, without a trace of shame or judgment. This was both overwhelming and freeing. I started asking myself, “What if I stopped pretending that I don’t suffer from depression? What could that do for my life?

I began taking a different approach to my mental health. I had lived with anxiety and depression for so long, but had never truly educated myself about it. As I immersed myself in the subject, I found I was more open to the possibility of acknowledging the impact it had on my life. I also began shedding some of the shame I had carried. I allowed myself to re-channel the energy I had been using to hide my condition, into keeping myself well.

Since 2014 I have continued to volunteer with the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention, expanding my role and serving as the chair of the Fargo-Moorhead Out of the Darkness Walk, as well as becoming a presenter for AFSP’s Talk Saves Lives™ education program. But what I have offered AFSP in terms of my time has been far surpassed by what I have received in return: a sense of hopefulness for the days that are in front of me, a belief that I can impact my mental health no matter my past, and a feeling of genuine belonging among my peers.

To find an Out of the Darkness Community Walk near you, click here.